Céline Sciamma’s period drama and heartbreaking love story Portrait of a Lady on Fire makes audiences behold a supreme level of artistic endeavor. Though it is a lesbian love story, it represents the signage of universal love. This film is about a story of love, politics of love, and a philosophy of love. Even though separation is quite inevitable, but the relationships can never be terminated. The bond keeps flourishing in absence, silence, and distance. Some love stories never end.

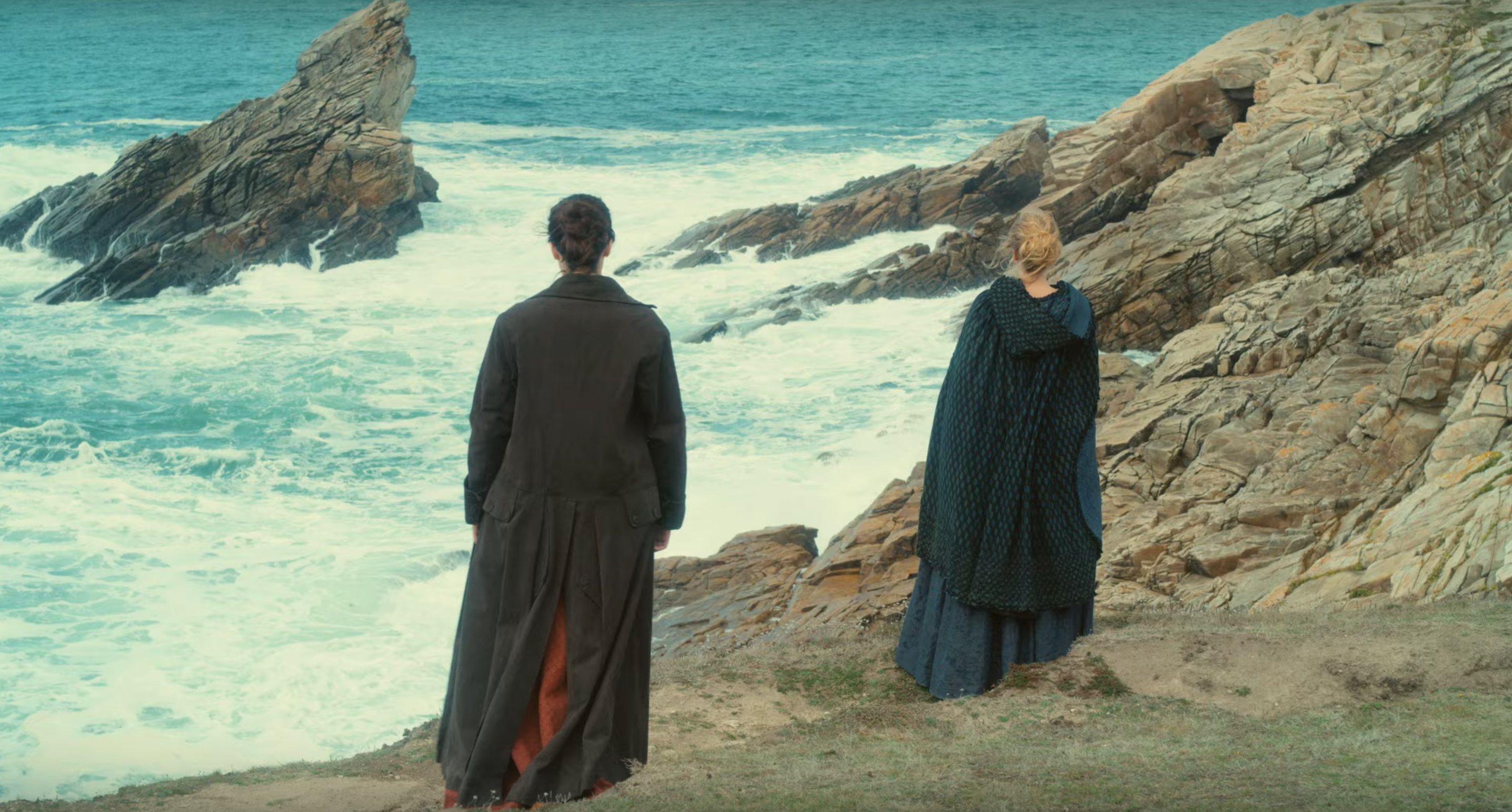

The film is set in the coastal town of Brittany in the late 18th century France around the 1760s. The eldest daughter of the family had committed suicide. So, the family brought back the younger daughter named Héloïse (Adèle Haenel) from the convent. Héloïse is about to be married to a Milanese nobleman, but she does not agree to this match. A portrait of the bride needs to be sent to the groom to fix the match. A painter was commissioned earlier to paint her portrait, but she did not agree to pose for the portrait.

A female painter, Marianne (Noémie Merlant), has been commissioned to paint Héloïse’s portrait without revealing the purpose and behaving as a companion to her. So, Marianne needs to memorize the minute details of Héloïse’s physical and facial features and paint the portrait. While onboard the boat, Marianne’s painting crate falls in the water, but no male boatman jumps into the sea. Marianne jumps into the sea risking her life and rescues her crate. This scene may not portray hatred towards the male but surely depicts strong female desire and will.

Marianne and Héloïse start talking to each other and they slowly become part of each other’s life and world. She observes Héloïse carefully and paints the portrait. She feels guilty for not revealing to Héloïse about the portrait and finally shows her the portrait. As Héloïse criticizes the portrait, Marianne destroys the portrait. Héloïse agrees to pose for Marianne, which surprises her mother, the countess (Valeria Golino).

The countess leaves Brittany for Italy. Marianne and Héloïse become closer to each other and their bond grows stronger. They spend quality time playing cards, reading storybooks, and listening to music. They help housemaid, Sophie (Luàna Bajrami), to get aborted. Héloïse, Marianne, and Sophie along with other women join a bonfire ceremony, where the women sing a Cappella song. Héloïse’s cloth catches fire.

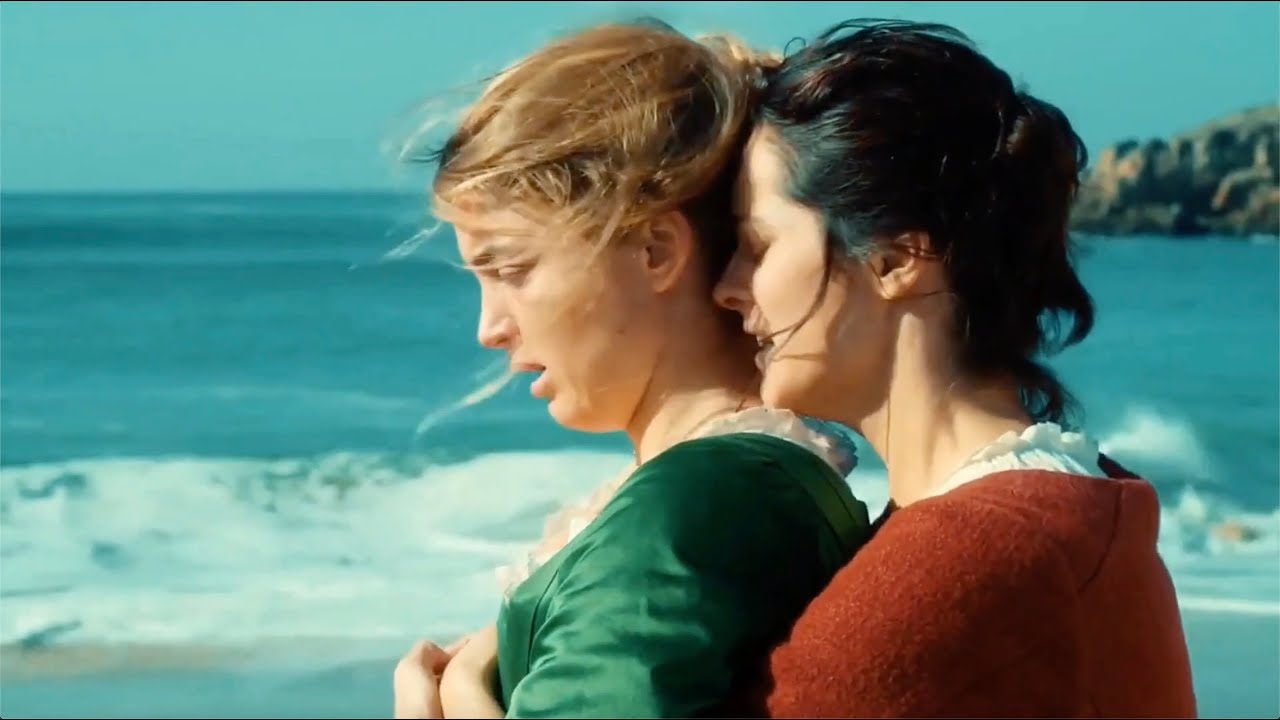

The next day, Marianne and Héloïse go to the cave near the seashore and kiss each other. They are now covered under a sensuous romance, which continues throughout their activities and conversations. The countess returns from her trip and Marianne is about to bid adieu. She is haunted by the image of Héloïse in a white wedding gown. Before leaving, Héloïse asks Marianne to turn back and she sees Héloïse exactly in the wedding gown, which haunted her for several days. Marianne departs and a breathtaking and heartbreaking love story comes to an end.

Years later, Marianne reveals to her students that she saw Héloïse two more times. The first time, she saw a portrait of Héloïse in a painting exhibition. On the portrait, Héloïse was seen holding a book showing only page 28, wherein Marianne painted a self-image during their stay together. The second time, Marianne saw Héloïse, although Héloïse did not see her, in a musical concert, which was playing “Summer” part of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons. Marianne played the same for Héloïse during their stay together.

Claire Mathon delivers yet another breathtakingly beautiful cinematographic masterpiece in 2019 along with Mati Diop’s Atlantics. Irrespective of static or dynamic shots, her camera captures some of the most beautiful images ever captured for motion pictures. If Portrait of a Lady on Fire is paused at any moment and a screenshot is printed, it will make a mesmerizing image or portrait. The camera flows slowly in rhythm with the dialogues. The camera moves or is placed in such a way as if it is observing the characters with minute details. Claire Mathon’s inquisitive camera lingers on the characters and unfolds innermost behaviors and identities.

The usage of light throughout the film is highly praiseworthy. Charcoal light, candlelight, wooden fire, and oil lamps are used to illuminate the faces as if those are burning amidst the darkness of the manor. The images are so vivid and brightened that those can signify the late 18th century France throughout the runtime of the film. Dorothée Guiraud’s costume design and Quinet Sebastien’s hair-styling complement the setting of the film in the late 18th century. Director Céline Sciamma herself is an uncredited costume designer. Even though minimally used, music composed for the film is efficient and the Cappella song during the bonfire ceremony is haunting. The “Summer” part of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons orchestra is used efficiently.

Portrait of a Lady on Fire is also about the female gaze or maybe much more than that. The painter observes her subject minutely and so as the subject. There is a scene wherein Marianne says to Héloïse, “When you are moved, you do this with your hand; when you are embarrassed, you bite your lip; and when you are annoyed, you don’t blink.” In reply to Marianne, Héloïse says, “When you do not know what to say, you touch your forehead; when you lose control, you raise your eyebrows; and when you are troubled, you breathe through your mouth.” There cannot be a better example of observing and knowing each other.

One of the most important parts of this film is Céline Sciamma’s screenplay. The dialogues are slow-paced and the characters take time to become part of each other’s world. The screenplay is so strongly woven that no word appears to be an extra. Adèle Haenel as ‘Héloïse’ and Noémie Merlant as ‘Marianne’ are dynamic, sensitive, and overall amazing. They are perfect fits for the roles assigned to them. Their expressions throughout the film are so real that the story emerges more of a real-life event than plotted drama. Céline Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire can easily be placed in memories for years to come.