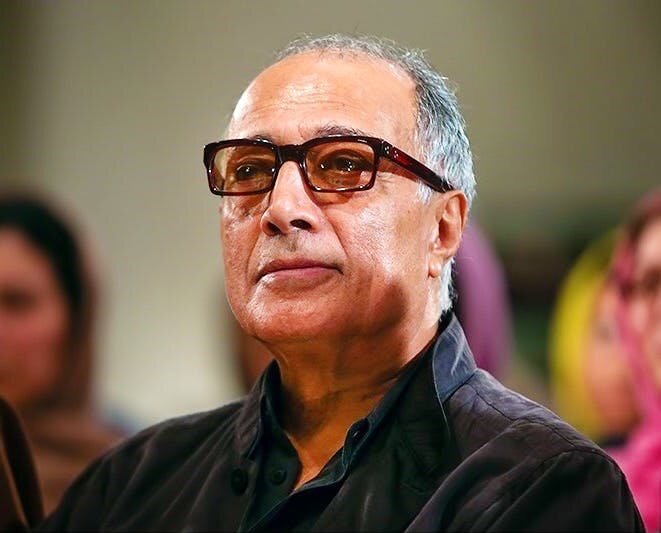

Abbas Kiarostami received widespread critical acclaim over time not only in Iran but across the world. He began his filmmaking journey in the 1960s but started receiving international recognition from Where Is the Friend’s Home? onwards. He was one of the very few filmmakers who did not leave Iran after the Islamic Revolution in 1979. When his peers fled the country, he remained in Iran and famously said, “When you take a tree that is rooted in the ground and transfer it from one place to another, the tree will no longer bear fruit. And if it does, the fruit will not be as good as it was in its original place. This is a rule of nature. I think if I had left my country, I would be the same as the tree.” He believed that his life, culture, and filmmaking endeavors are deeply rooted in Iran and its people. His films are not overtly political, and his objective was to represent Iran and its people through his films but not fighting the govt deliberately just for the sake of political gains. He was never a political opportunist and had no ambition in politics. As an artist, he only raised concerns about ordinary Iranians through his films. The love that he preached, the sympathy that he showed, and the belief that he had in humanity can never be forgotten.

Iranian People and Culture:

Kiarostami’s films are reflections of the Iranian people and their culture. Barring ABC Africa, Certified Copy, and Like Someone in Love, his films are purely Iranian. He depicted a rural schoolboy’s civic duty to return his friend’s notebook in Where Is the Friend’s Home?. The resilience of rural Iranian people after the 1990 Manjil-Rudbar earthquake is shown in Life and Nothing More… The hardships of Iranian women are portrayed in Ten. Most of Kiarostami’s works are filled with the love, sorrow, resilience, peace, happiness, and tears of ordinary Iranians.

Landscapes of Rural Iran:

Kiarostami’s films capture picturesque views of rural Iran. Those are filled with an abundance of natural beauty. The most important aspect of the rural Iranian landscape captured in his films is zigzag rural roads mostly in hilly areas. Ahmad goes to Poshteh from Koker through a zigzag hilly road in Where Is the Friend’s Home?. Farhad Khedarmand in Life and Nothing More... and Badii in Taste of Cherry drive through zigzag rural roads. Kiarostami’s films are filled with zigzag rural roads, hilly countrysides, vast wheat fields, woods, multiple villages, and a plethora of natural beauty of rural Iran. Multiple film critics opine that Where Is the Friend’s Home?, Life and Nothing More…, and Through the Olive Trees form a trilogy, which is termed as Koker Trilogy as all of them are connected to the northern Iranian village named Koker. However, Kiarostami suggested that the latter two tiles and Taste of Cherry form a trilogy as all of them portray the preciousness of life.

Use of Children:

In his multiple films, Abbas Kiarostami used children as protagonists. A schoolboy’s civic duty to return his friend’s notebook is portrayed in Where Is the Friend’s Home?. The filmmaker Farhad Kheradmand travels to Koker driving his car in search of Ahmad, the child protagonist of Where Is the Friend’s Home. There is a prolonged conversation between the lady driver and her son about her divorce in Ten. The journalist Behzad is accompanied by Farzad in The Wind Will Carry Us. In almost all of his films, Kiarostami used children as protagonists and side characters. Children bring freshness to films, which look real and portray the core essence of his art. The innocence and simplicity of those children paint Kiarostami’s imaginations neutrally on the silver screen. He always remained true to himself and the outside world.

Philosophical Aspects of Life:

Kiarostami was a true artist as well as a philosopher. He depicted multiple aspects of life through his films. Humans who experience life very closely can only have the true essence of life. His films not only highlight the lives and culture of ordinary Iranians but also portray human emotions and virtues universally. Kiarostami’s films are filled with philosophical aspects of life like love, peace, suicide, afterlife, spirituality, separation, death, communion, happiness, solitude, break-up, rejections, agonies, loss, etc.

Neorealism:

Kiarostami was deeply inspired by Italian neorealism. It was quite obvious that it had a profound impact on his filmmaking styles. Like neorealist masters Roberto Rossellini, Vittorio De Sica, and Luchino Visconti, Kiarostami mostly used non-professional actors, filmed on locations with natural lighting, used sync sound, and made the films with minuscule budgets. His filmmaking principles were largely impacted by the life and culture of ordinary Iranians.

Cinema as Imagination:

Kiarostami never showed everything on screen. He believed that if all the details are shown on the screen, then there will be nothing for the viewers to imagine. The necessary details that are integral parts of classical Hollywood filmmaking are very often missed in his films. In the last scene of Through the Olive Trees, Viewers are invited to imagine Tahereh’s response to Hossein. Multiple characters in The Wind Will Carry Us are not shown on screen at all. Kiarostami did not show whether Badii has actually committed suicide or not in Taste of Cherry. His films can be inferred as showing without showing. Even though multiple characters or events are not shown on the screen, viewers can feel them. Movies are one of the most dynamic mediums of art and as a true artist, Kiarostami always invited viewers to connect the dots.

Use of Automobiles:

A very few filmmakers could use automobiles as efficiently as Kiarostami did. Those were an integral part of his films. His films define the concept of automotive cinema. He used automobiles as a dynamic place to experience the outside world still being inside. Two characters can have a conversation without focusing much on each other and being on their own. Many of his films have conversations unfold inside cars, and those are filmed by stationary mounted cameras. When the characters are filmed from the exterior, the surroundings are reflected on the windshields. The viewers can see the interior and the exterior together. This is very often seen in his films. Kiarostami loved automobiles as a great place to talk.

Issues of Women:

Kiarostami always stood firmly against the oppression of women in modern Iran. He was a strong believer of women’s rights. In Ten, he raised his voice against divorce and separation mostly initiated by men. In The Wind Will Carry Us, he shows that a woman can run a teashop all alone. His heart feels for the lady who starts working just a day after her delivery. Kiarostami dreamt of a society where men and women would be having equal rights.

Experimentation:

Kiarostami always experimented on his filmmaking craft and tried a create a new language of cinema. He filmed Ten with two stationary mounted cameras inside the car but he was not present. He gave directions to the actors before they drove through the streets of Tehran. He shows through Ten that a world-class film can be made without the director’s presence on the set. In Shirin, the actresses were filmed first, and then the story was selected, and the soundtrack, dialogue, and music were created. The emotions of the actresses matched with the soundtrack, dialogue, and music. Five Dedicated to Ozu is devoid of any dialogue, story, and music. It consists of five long shots on the seashore of the Caspian Sea.

Camera Gaze:

Instead of static, Kiarostami always favored the dynamic mode of filmmaking. His camera was never restricted and focused on a place and character, rather he used to observe the surroundings through his meditative camera. He allowed his camera to capture hills, alleys, woods, zigzag rural roads, passers-by, villages, and almost everything that surrounds the characters. Viewers can experience the outside world still being able to hear the conversations between the characters. Kiarostami was able to establish the relationships between his characters and the surroundings they dwell in.

Poetic Cinema:

Kiarostami was a master of poetic cinema. His films not only told stories but also created a magical world with images and sound. Kiarostami dug deeper into life and portrayed the true essence of it through his films. One of his films Five Dedicated to Ozu does not have a story at all. Multiple times, he followed non-linear structure for his films. He believed life can not be understood and portrayed fully just by words. Human emotions can never be fully converted into words. Those need to be felt deep down in our hearts. Kiarostami painted his imaginations through his films that often lack proper narrative structure. He invited his viewers to be involved in his poetic world. In The Wind Will Carry Us, he directly used poems written by Forough Farrokhzad and Omar Khayyam. The title itself is the namesake of Farrokhzad’s poem The Wind Will Carry Us.

Docufiction:

Kiarostami’s films are fully neither documentaries nor fictions, rather a mixture of both, which can be termed as docufiction. In Life and Nothing More…, he captured the destruction and devastation caused by the infamous 1990 Manjil-Rudbar earthquake that took over 40,000 lives. However, the film was not shot immediately after the earthquake. Kiarostami shot the film a few months after the earthquake. Multiple scenes in the film were recreated during filming. So, it is neither fully a documentary nor quite a fiction. Kiarostami portrayed different aspects of life realistically through his signature docufiction mode of filmmaking. He followed this style for almost all of his films.

Simplicity:

Kiarostami believed in the minimalistic approach of filmmaking. Complex action or chase scenes are never really part of his films. He followed a very simple and naturalistic way to depict the lives and culture of ordinary Iranians. He himself once said, “Technique just for the sake of Technique is a big lie. It does not answer real feelings and needs.” He was able to establish a very simple yet strong relationship between humans and nature.

Panoramic Long Shots:

One of the most important features of Abbas Kiarostami’s filmmaking style is extremely wide-angle panoramic long shots. He captured the panoramic views of the hilly areas, woods, zigzag rural roads, and villages by long-distance overhead shots. His focus was on the surroundings as much as the characters. Multiple times, viewers can see panoramic views of rural Iran with the audio conversation of the characters in the background.

Bright Color:

Kiarostami often used bright colors for the landscapes. A very few filmmakers could paint nature and its wonders the way he did. Those vibrant images became one of the main features of his filmmaking style. Bright colors made his films look lively and liberating. He was able to match the colors of nature with life, which is colorful itself.

Visual Distancing Method:

One of the signature filmmaking styles of Abbas Kiarostami was the visual distancing method. In this method, the characters are not shown on the screen, but the audio of their conversation is played in the background. The meditative camera gazes through the hills, woods, villages, and zigzag rural roads. Using this method, Kiarostami matches the characters inside the cars and the surroundings, as if the public and private spaces are mixed together. In the panoramic long-distance overhead shots, the cars are seen being driven through the hilly roads.